Robots and Good Jobs on the Other Side of Covid-flation

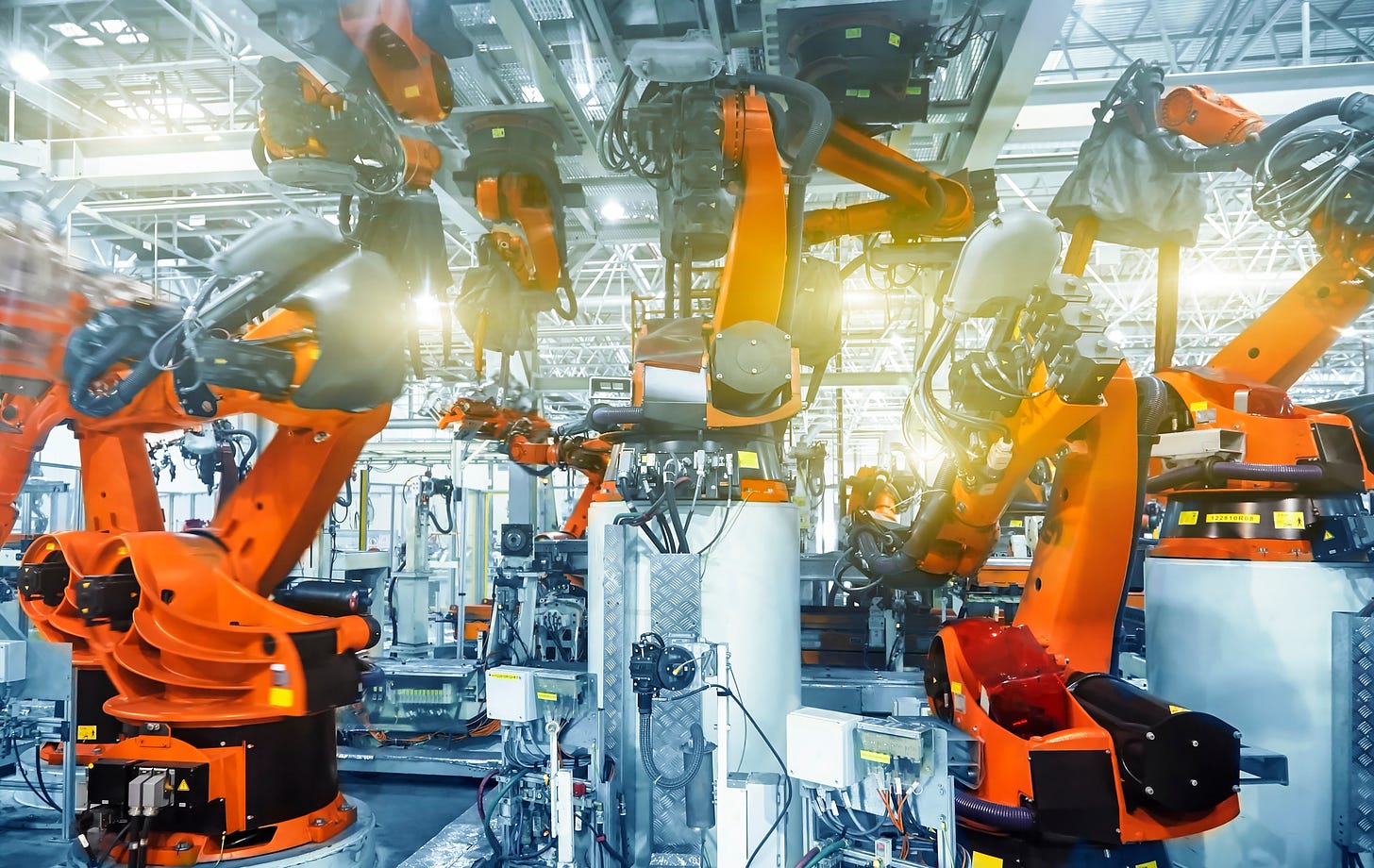

The Wall Street Journal reports that “Robots are turning up on more factory floors and assembly lines as companies struggle to hire enough workers to fill rising orders.” Post-pandemic labor shortages are newly apparent in every industry, from baristas to bank tellers. Labor shortages in hard industries are hardly new, however, as any manufacturing or construction executive would have told us for years. Economists, meanwhile, can never seem to agree on whether robots are good or bad — nor on automation more broadly.

According to the Journal:

Daron Acemoglu, an economics professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said factories’ increasing reliance on automation will lead to an oversupply of human labor that will drive down wages in the years ahead, unless other U.S. industries can absorb displaced manufacturing workers.

“Automation, if it goes very fast, can destroy a lot of jobs,” Mr. Acemoglu said. “The labor shortage is not going to last. This is temporary.”

At this point in the American economic story, should we really be worried about more domestic investment in high-tech capital goods? Robots and crazy labor markets are just two facets of bigger, more fundamental shifts underway. Vulnerable supply chains and a rethinking of trade with China have intensified focus on domestic manufacturing and distribution. The acceleration of remote work points in the other direction, tending to reinforce the decades-long trend of globalization. One shift says place matters more; the other maintains place matters less. Combined, however, these alternate atoms-and-bits trends may help us achieve the productivity boom I’ve suggested might be around the corner.

I think robots will actually be a central facet of an American hard industry renaissance—one that will be good for productivity and for workers.

Acemoglu argues automation can reduce employment, showing geographic correlations between robots deployed and jobs lost. But I think this ignores the complex interplay of technology and trade during the epochal Asian manufacturing shift of the last 40 years. History shows that, over time, more technology leads to more vibrant economies and higher paid workers.

The problem is that US tax and regulatory policies, weighed against global costs, made it increasingly difficult to build things domestically. Robots were the only way many manufacturers could justify US production at all. For marginal businesses, however, there was no rationale to build in America.

Free trade made the world richer overall, delivering affordable products to Westerners and middle-class lifestyles and freedoms to billions of people around the world. Meanwhile, however, the US probably overshot the outsourcing mark.

The gigantic trade deficit per se wasn’t the problem. A trade deficit implies a capital surplus; dollars which American consumers send to China must be reinvested in the US. Far too much of that inbound investment, however, went into US government debt, and thus profligate spending, instead of productive domestic capacity.

The 2017 tax reform was a crucial first step toward more domestic capital investment. With the pandemic and inflation jumbling our economy, it will take a few years to see big results, but the initial signs are promising. Although we reduced the corporate tax rate to 21 percent from 35 percent, business tax receipts are now soaring. Regardless, we need an array of smarter regulatory, energy, environmental, educational, and infrastructure policies to reignite the domestic shift so many policymakers insist they desire. We can’t merely mandate or subsidize unprofitable ventures. We must allow profitable building in the US, and as I’ve argued many times before, I think the best way to do that is with more technology, not less.

As I wrote previously:

Infusing more information technology into the physical industries is the chief way we can turn low-value-add old industries we pushed off shore into high-value-add industries we want here at home. In other words, robots are the friends of skilled labor. Without them, we can’t profitably build at home at all.

The use of robotics, computer vision, additive printing and artificial intelligence to boost our construction and factory capabilities will be central to any hard industry resurgence.

The goal is not to bring back old industries and old jobs with old capital goods. The goal is to help traditional industries — manufacturing, transportation, retail, wholesale, health care, food, education, energy, etc. — to transform and create new jobs, using a mix of physical capital and cutting edge technology.

The pandemic and inflation interrupt, confuse, and depress. In other ways, however, these challenges clarify our thinking, recall our ingenuity, and potentially set the stage for an American renaissance.

This article originally appeared at AEIdeas.