After a July 14 launch and several weeks of positional orbiting, India’s Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft landed safely at the Moon’s South Pole earlier today. A rover will now survey the region, thought to contain large amounts of water ice, which might be useful in future space missions. The U.S., Russia, and China previously visited the Moon, but India is the first to reach its South Pole. A Russian module was scheduled to complete its journey to the South Pole on August 21 but crashed.

The re-race to space follows several decades of relative quiet. Beyond delivering primary capabilities, such as wider Internet coverage on Earth, the space renaissance is spinning off technological advances and sparking geopolitical maneuvers.

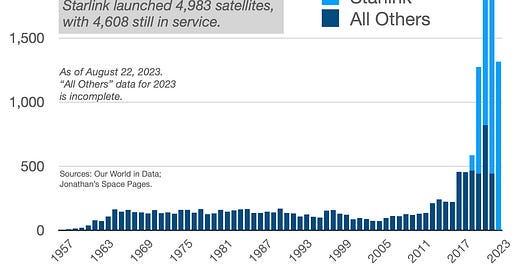

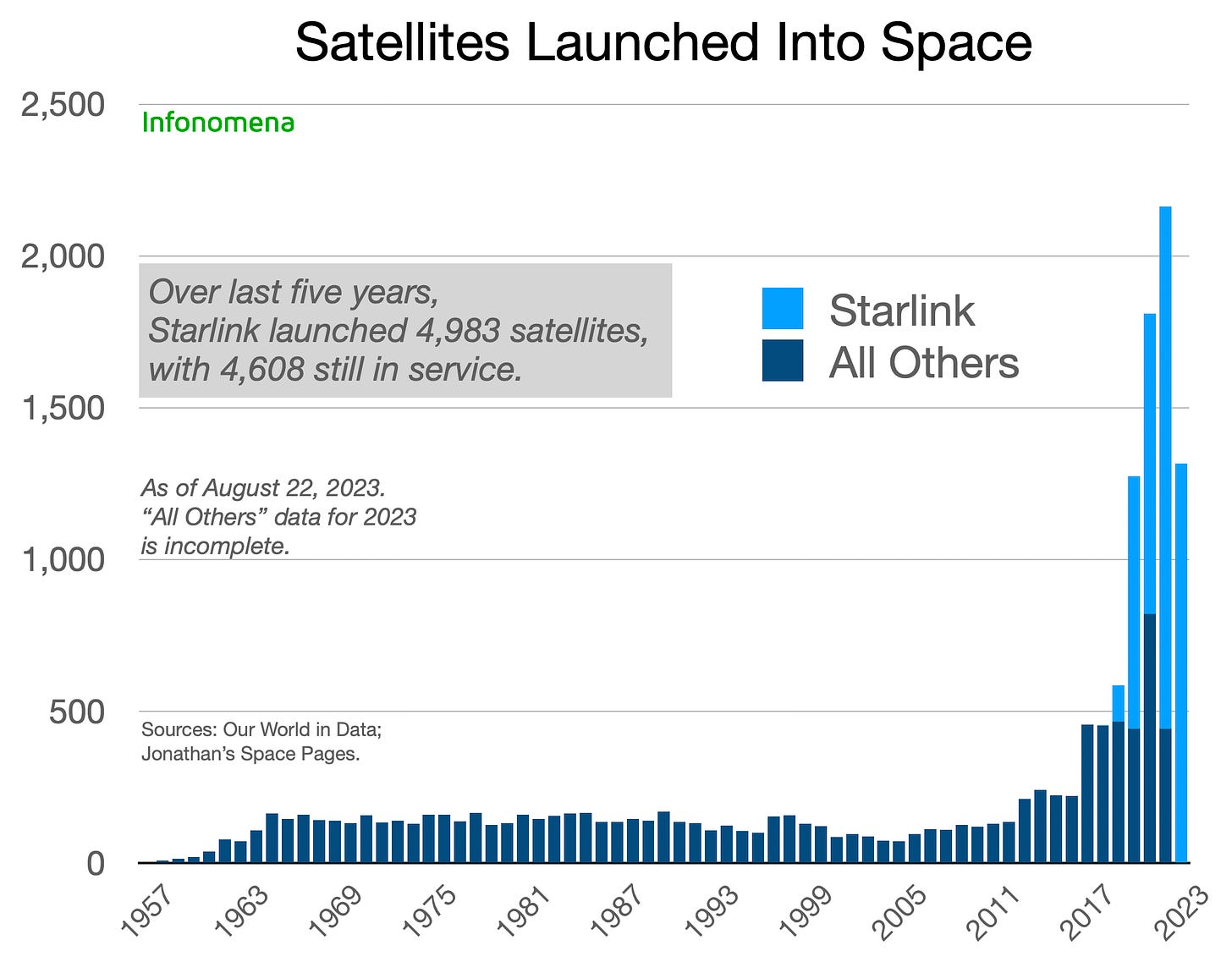

One way to see the space boom’s magnitude is to merely count the number of satellites delivered over the years. For more than five decades since Sputnik in 1957, the world averaged 100-200 satellite deliveries per year. Most of these were military, scientific, telecom, and broadcast. An inflection in 2017 moved us toward 500 annually. In 2020, we sped past 1,000, then surpassed 2,000 last year.

Most of this leap is due to Elon Musk’s constellation of small Starlink low-earth-orbiters, which form a mesh to deliver Internet access across much of the globe. Starlink, the satellite company, is a division of of SpaceX, the larger rocket company. In just five years, Starlink has put up 4,983 satellites, 4,608 of which are active. Low-earth-orbit LEOs will of course be far more plentiful than geostationary GEOs, which dominated the early decades of satellite history. (LEOs orbit at around 550 km, GEOs at 35,786 km, or 65 times further from Earth.)

SpaceX is far bigger than Starlink. In fact, SpaceX may now be delivering around 80% of all payloads to space, for both private and government customers. Speed, price, reusability. These traits have not traditionally defined space, but they are now redefining extraterrestrial economics.

The Wall Street Journal reported on August 17 that SpaceX generated $4.6 billion in revenue in fiscal 2022 and that it may have turned a profit for the first time early this year – “$55 million in profit on $1.5 billion in revenue during the first quarter of 2023.” SpaceX is still privately held but is said to be valued at $150 billion.

For Musk, however, no good deed goes unpunished. A new profile of Musk in the New Yorker insinuates that his quick delivery of Starlink satellites to Ukraine, after the Russian invasion, was less than noble. Because the agile satellite system had proved so useful to Ukraine’s efforts – “the essential backbone of communication on the battlefield,” in fact – and because Musk retained the hypothetical ability to turn the system off, the New Yorker suggests maybe such capabilities should not be left in private hands.

All of Musk’s properties are under siege. Twitter, the pseudocrats say, spreads dangerous misinformation, and Tesla’s EV charging stations are a monopoly. The Musk companies are now critical infrastructure and may be too important to be left to one man’s whims. You can see where these self-serving storylines are going. Maybe it’s because Musk is challenging the status quo and building alternative, parallel networks evading pseudocratic control.

Meantime, China’s and Russia’s space capabilities are impressive and growing. If not for SpaceX reinvigorating U.S. capabilities, NASA and the larger American space program might have been left in the terrestrial dust.