"Our Institutions Are Too Sterile."

Elliott Parker delivers a diagnosis of corporate stagnation – and a strategy to revive creativity and growth in the A.I. era.

The Illusion of Innovation by Elliott Parker.

Today’s historically high-stakes battle in Washington, D.C., highlights a perennially frustrating phenomenon: Incumbent organizations resist change.

Even successful ones, like the United States of America.

Sclerotic governments may not be surprising. Maybe they’re even the rule. But no organization is immune. Private institutions and companies are supposed to be more nimble and creative. Too often they are not. In the last decade, organizations of all types seem to have retreated further from the frontiers of adaptability and innovation, preferring instead safety, compliance, and hyper-conformity. They say they want to innovate. They may even believe it. But inertia and internal incentives often make true innovation nearly impossible.

Why does this pattern persist?

In 1997, Clayton Christensen, a professor at Harvard Business School, gave us The Innovator’s Dilemma, a bolt from the blue that demolished all the worst stereotypes of lazy business books and cliches of “innovation.” With data from the disk drive industry, Christensen developed a deep, quantitative, counterintuitive framework of technology, business management, and institutional dynamics.

Genius CEOs in high growth industries, Christensen wrote, could do everything right – and yet still succumb to seemingly inferior innovations bubbling up from below. In fact, they would fail precisely because the customers they competently served, metrics they expertly met, and profits they dutifully delivered blinded them to misfit challengers and their “good enough” toy products. Meanwhile, entrenched employees and fiefdoms would mount antibody immune attacks on anticipatory efforts to build new products, enter new markets, or defend against upstart competitors. We can’t risk cannibalizing successful existing products!

The examples are endless: Tiny, inexpensive Japanese cars over Big Three behemoths. Digital cameras over film. Blogs and podcasts over newspapers. And most recently – Nvidia over Intel.

Now, a former colleague of Christensen has built on his promethean insights. Elliott Parker, like his late boss, is mild-mannered but razor-sharp. Parker and his venture studio High Alpha Innovation help big companies launch start-ups in an attempt to find, in the words of Christensen’s second book, The Innovator’s Solution.

Parker’s new book, The Illusion of Innovation, takes the next step. Which is much needed, because A.I. is already turbocharging all the incentives, themes, and dynamics Christensen identified nearly 30 years ago.

A.I. will turbocharge The Innovator’s Dilemma.

Parker thinks most big companies are too cautious. And when they do attempt to “do innovation,” their efforts too often resemble playing house.

Record levels of dividend payments and stock repurchases tell part of the story. “Between 2010 and 2019,” Parker writes, “US firms distributed $4 trillion in dividends and $6 trillion in buybacks; in total, they distributed about $4 trillion more than they raised.” Companies are obsessed with returns on invested capital and assets – measured by RONA, ROIC, and IRR. Financial engineers ruthlessly focused on efficiency are delivering great near-term results. “In 2022 alone, companies listed in the S&P 500 executed nearly $1 trillion in share buybacks – a record number that was twice the amount of dividends in the same period.”

From one perspective, giant cash returns are a sign of success. Most shareholders won’t complain – at least in the short-term. But the long-term matters, too. From this perspective, huge buy-backs may be signs of timidity. Companies can’t find big new projects in which to invest. They don’t have the courage to launch experimental new products.

Over the long-term, the failure to reinvest depletes a company’s vitality and ability to compete with upstarts. “The optimal amount of capital inefficiency…is not zero,” Parker writes. “Stop treating capital as a scarce resource.”

Are companies already heading this message? Big Tech’s epochal investments in A.I. infrastructure – totaling hundreds of billions of dollars in 2025 alone – may be one sign, in at least one industry, that intrepid investment is making a comeback.

Game Machines

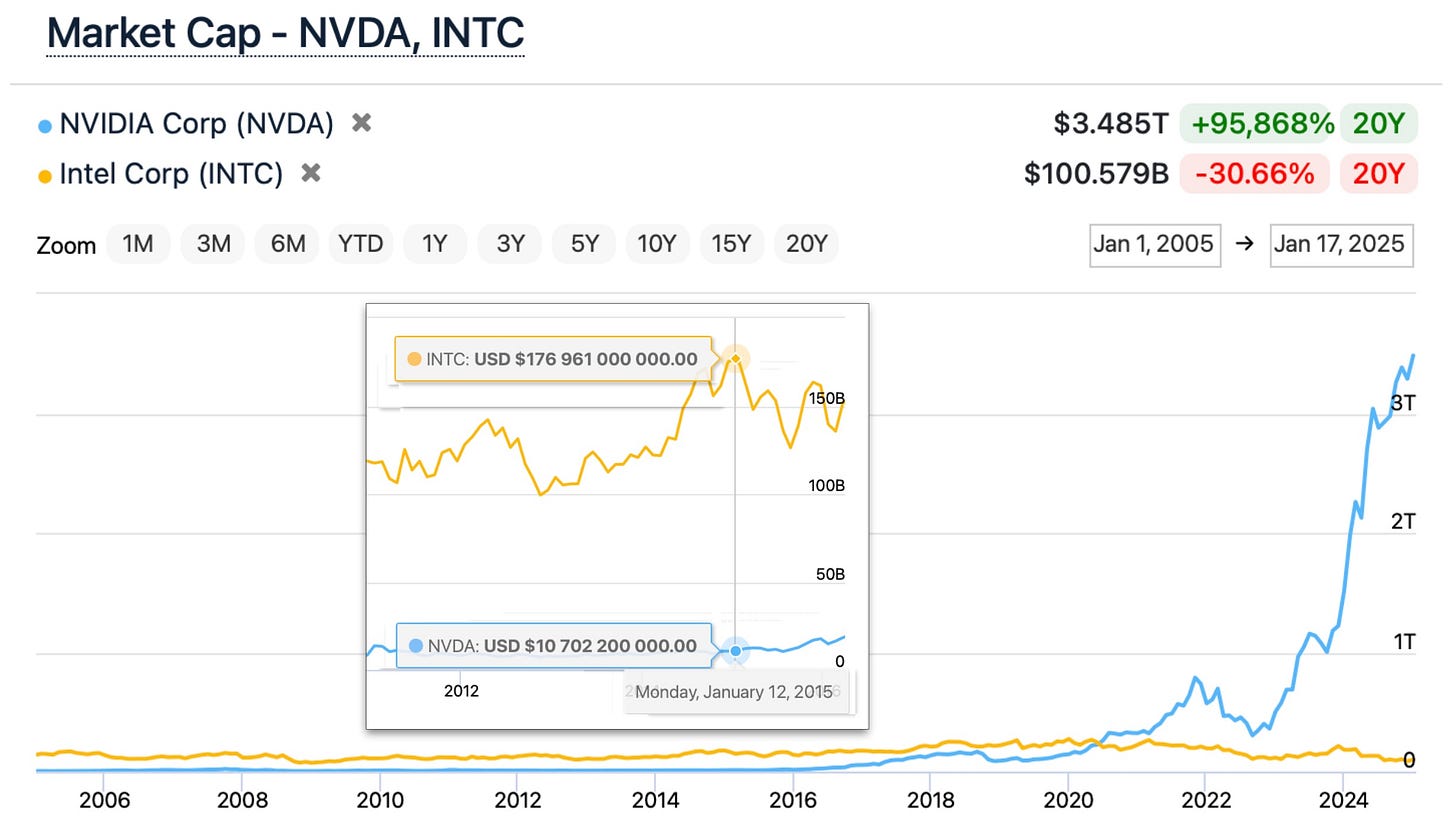

Intel, on the other hand, is a perfect example of a company which waited too long or couldn’t otherwise escape the innovator’s dilemma. Intel, after all, was an original hero of Silicon Valley. It made chips for serious computing – PCs, laptops, and servers. Little Nvidia, meanwhile, made chips for video game consoles – mere toys.

For decades, Intel’s market value was 10-15 times larger than Nvidia. As recently as 2015, Intel was 16.5 times larger. In 2020, however, Nvidia caught Intel and now, as the central silicon provider of the A.I. juggernaut, sports a market value of $3.3 trillion, 33 times larger than Intel.

The irony will not be lost on those who remember the famous January 25, 1999, cover story in Forbes magazine, featuring Intel’s great CEO Andy Grove alongside his “big thinker” – Clay Christensen. Nvidia, founded in 1993, was still just a baby firm making graphics chips for Sega game consoles. It had gone public just three days prior to that issue of Forbes.

It turned out Nvidia was perfectly positioned for the exaflood. In a world of real-time data flows, first with tsunamis crossing the Internet, then unimaginably large A.I. training and inference workloads, Nvidia’s parallel architecture proved ideal. Intel’s serial computing CPUs were ill-suited to massively parallel computing. In order to exploit today’s A.I. data center explosion, Intel would have had to make the big switch to GPUs 10 years ago – when A.I. was still a dream and video games were so much less serious than PCs, laptops, and servers.

The Institutional Dilemma

The broader import of these ideas can be found across all of society.

The multiple Covid catastrophes were perhaps the capstone of an era of institutional underperformance, if not outright failure. For example, thousands of intellectuals working in dozens of medical institutes and public policy research centers – or “think tanks” – somehow got almost every scientific and policy topic wrong. From the origin of the SARS2 virus to lockdowns, from face masks to inflation, from “natural immunity” to vaccine mandates, entire armies of health and policy experts united behind safetyism and compliance with top-down authority. They failed even to consider the most rudimentary cost-benefit analyses, let alone the more demanding work of biology and immunology.

Even the conservative and libertarian think tanks defended, or at least acquiesced to, the deepest and broadest attack on free speech, via digital censorship, in American history. How could this happen?

Many factors contributed to the calamity. Hyper-conformity, lack of imagination, and censorship were key. The establishment experts’ total ignorance of, or disdain for, dissident scientists and under-credentialed analysts blinded them to alternative viewpoints and better solutions. Just as toy products surprise serious companies, the rebel Covid analysts trading information on Twitter and in group chats, mostly in their spare time, totally outperformed the think tanks, medical schools, and and public health agencies, despite (or perhaps because of) their endless credentials and billions in secure research funding.

The Covid failures created the opening for upstart organizations, such as the Brownstone Institute and the Independent Medical Alliance. These rag-tag groups performed real scientific and policy research, and, in retrospect, got most things right.

Parker’s insights are instructive. “Our institutions are too sterile,” he writes.“Organizations need more messiness to achieve more insights.” It turns out that up-tight perfectionism and risk-aversion often lead to myopia, and even catastrophic mistakes. After an era of neurotic banality, organizations need more personality. More originality.

The A.I. Acceleration

All these institutional challenges and opportunities are about to get their biggest test yet. New A.I. tools are already remaking the software industry and will soon disrupt every task, job, firm, and industry. At speeds we’ve never seen.

Single person firms may be common. Small teams will do in months what used to take 100 employees years. Non-technical people will build new products and companies as if they were computer geniuses. An explosion of micro-entrepreneurship may challenge every firm and organization.

Parker offers rough rules for big companies trying to launch new businesses: if there are more knowns than unknowns and the idea is core to your business, form and empower a new in-house team. When, on the other hand, the technology or business challenge is exploratory or highly uncertain – if it’s a “learning challenge” – launch an unconstrained external start-up. The former core innovation efforts, moreover, can be funded as operating expenses, while external ventures can be funded through the balance sheet – thus preserving those sacred metrics.

In the end, Parker doesn’t pretend to have solved the innovator’s dilemma. It is, after all, a never-ending journey of multifaceted, ever-changing variables and feedback loops. Instead, Parker describes deep institutional challenges you are likely facing. And he provokes us to think about how best to deploy a key tool of the emerging A.I. acceleration: “finding ways to empower small teams – through better incentives – to conduct more of the experiments we need: faster, weirder, and cheaper.”

Doesn’t that remind you of the 19-year old DOGE hackers, led by a famous rocket-engineer-car-maker-social-media-mogul, who this very minute are, at record speed, attempting to remake the world’s largest organization? Love it or not, that’s the future.